The Impact and Enterprise post-graduate course at the University of Canberra is unique in Australia in placing creative industries and the creative and cultural economy in the broader landscape of the wider impacts of creativity and culture - both economic and social. It starts from the premise that what the broader social and economic roles of creativity and culture have in common is that a focus on the economic role of creativity and culture is similar to the focus on its community role – both spring from recognition that creativity and culture are integral to everyday life and the essential activities that make it up. In March 2021, as the course entered its third year, I gave a talk to the students about where it came from.

Increasingly I realise that everything is connected – if only we are able to recognise how and benefit accordingly. The ripple effects of creativity and culture reach far further than we might expect.

At one point one of my managers in the public service commented with a note of disapproval that I seemed to have done lots of different jobs in my career. What she didn’t realise was that I had done the same job, but in lots of different places. I was surprised that she didn’t see that because one of the things I loved most about my time in the Commonwealth public service was that every couple of years – if not months – you would find yourself doing something new.

You would never hear about this, but at the height of the pandemic, one of my former Arts colleagues found herself working around the clock in a task force set up to liaise with the major supermarkets to ensure that supplies didn’t run out, as a major attack of moronavirus stripped the shelves of toilet paper.

Working in the arts and cultural area of the Commonwealth, we were moved about on a regular basis, as governments and Ministers changed. I managed to traverse more departments than I can count without ever applying for a transfer – Communications; Environment; Regional; Prime Minister and Cabinet; and finally Attorney General’s. After I left the Commonwealth in early 2014, I saw that Arts had moved back to Communications, before Communications itself was folded into another bigger department. Arts felt like one of those comets that circle the heavens before finally coming back to where it started – while terrifying the inhabitants on the planet below.

I mention this because, I’m sure like most of you, one step leads to another in the diverse and dispersed creative and cultural sector we work in or are interested in working in – and it all makes sense, somehow.

I got interested in and moved into marketing when I realised that so much cultural production was never reaching the potential audiences it could. Many of my peers in community arts went on to establish and teach the very qualifications that had never existed when they first started in the field.

'I’m sure like most of you, one step leads to another

in the diverse and dispersed creative and cultural sector we work in or

are interested in working in – and it all makes sense, somehow.'

Decades later I joined them by developing the Impact and Enterprise Unit at the urging of Professor Tracy Ireland, who recognised the need for the post-graduate course and came up with the very apt and expressive name. After all, why reinvent the wheel – that would definitely be wasted innovation. Better to learn what we can from what has already done and equip those coming forward to invent a completely new form of wheel.

Modern alchemy

In many ways the creative and cultural economy and creative industries remind me of that old quest of the ancient alchemists, seeking to convert base metals into gold. They went on to become chemists and pharmacists, converting medicines into a long, healthy life. My niece is a pharmacist at a major hospital in Adelaide and sometimes I think I expect her to wave a magic wand and make everyone better.

Creativity has that same slightly magical property, because it uncovers the connections between disparate things and makes one and one add up to three – when you’re not looking.

The Impact and Enterprise Unit reflects that. It tries to thread together widely disparate elements – creativity, society and community, the economy and jobs – highlighting how they are interlinked in the messy business of everyday life.

For professionals working in the cultural sector, who will be responsible for the direction the sector takes over the next 20 years, it is important to understand how creativity and culture plays an essential central role in Australia’s social and economic life, and why it therefore needs to be included on the main national agenda, recognising its integral relationship with major economic and social factors such as economic development, education, innovation, community resilience, social and community identity and health and wellbeing.

'For professionals working in the cultural sector, who will be responsible for the direction the sector takes over the next 20 years, it is important to understand how creativity and culture plays an essential central role in Australia’s social and economic life.'

The concept of innovation is important in this context. It helps place creativity firmly at the centre of economic and social development in the new knowledge economy which represents the future of Australia. We need to bring our use of the term ‘innovation’ back down to earth, understanding that it is about applied creativity. I am wary about other ways the language of business has taken over the worlds of community and government, for example with the focus on ‘customer service’. There is much that the community and government sectors can learn from business – and vice versa – but they are not the same.

In the case of creative industries, where we are talking about commercial organisations and operations, the language of business is relevant – in fact these creative enterprises often have lessons for business overall, for example in their clever use of the digital and online environment.

Creativity and culture are also closely linked to central social challenges Australia faces, such as responding effectively and productively to cultural diversity and to Indigenous communities. Creative industries depend on innovation and innovation occurs where cultures intersect and differing world-views come into contact and fixed ideas and old ways of doing things are challenged and assessed.

The dynamic connections of everyday life

There are three key concepts here – recognising connections, adopting a dynamic view and starting with the reality of everyday life.

Once you start to recognise connections, you can gain insights in specific challenging areas. The quest for sustainable economic futures for First Nations communities looks quite different when you think about the central importance of culture in generating economic independence. As embodied in Intellectual Property, culture becomes a rich seam of meaning which can generate income streams – just like iron or coal. Instead of simply thinking about labouring jobs in quarries or mines, it directs attention to other kinds of jobs.

You also see how cultural diversity is not a social problem to be solved, but a social and economic asset to be recognised and realised.

'Recognising the central role of creativity involves seeing the full, rich, interconnected, dynamic picture of everyday life. It’s not about simply economics, it about something much more fundamental – making a living.'

Once you adopt a dynamic view of culture, you start to think about cultural diversity not as a static aggregate of many diverse cultures, but as the constantly evolving interaction between those cultures.

Once you start with the reality of everyday life, then that abstract entity ‘the economy’, becomes the effort to make a living, society and community become the way people interact through living and expressing their culture. Recognising the central role of creativity involves seeing the full, rich, interconnected, dynamic

picture of everyday life. It’s not about simply economics, it about

something much more fundamental – making a living.

The broader impacts of creativity and culture

What the broader social and economic roles of creativity and culture have in common is that a focus on the economic role of creativity and culture is similar to the focus on its community role – both spring from recognition that creativity and culture are integral to everyday life and the essential activities that make it up. One crucial sector where this manifests is arts and health, but there are many more.

Creativity and culture show important promise in helping face central social challenges in Australia.

Case studies and anecdotal evidence, coupled with the experience of many years of the Indigenous culture programs managed by the Australian Government, was that involvement in arts and cultural activity often has powerful flow on social and economic effects for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. By building self-esteem and generating a sense of achievement, by developing a stronger sense of community, by increasing skills and capabilities through involvement in engaging activities relevant to modern jobs and thereby increasing employability, and by helping to generate income streams, however small, cultural activity can have profound long-term effects. It’s no exaggeration to say in many cases it changes lives.

The super power of diversity

The importance of diversity, including cultural diversity, has been recognised by influential figures in the public service, such as Martin Parkinson. Parkinson was the senior public servant who survived a near death experience at the hands of Tony Abbott, only to be resurrected by the incoming Malcolm Turnbull to become his new head of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

When Parkinson ran Treasury he recognised that to increase policy flexibility and innovation, he needed to expand the range of mindsets around him. Accordingly, as Peter Martin, Economics Editor for ‘The Age’ newspaper pointed out in a 2015 article about the experiment, ‘Parkinson not only set targets for the proportion of women in the treasury senior executive, he set about changing what Treasury valued to bring this about. When picking candidates for promotion or special projects, more weight was to be given to co-ordination and people skills and less to conceptual and analytic skills.’

'In a world where change is fast and widespread, can anyone afford not to mobilise all they have going for them – to survive, let alone to succeed? Diversity, including cultural diversity is a big part of that picture.'

Martin notes that this was because every enterprise needs both sets of attributes. Martin comments further, ‘Diversity matters because the more mindsets you can bring to creating something or solving a problem, the less likely it is you'll miss something out.’

In a world where change is fast and widespread, can anyone afford not to mobilise all they have going for them – to survive, let alone to succeed? Diversity, including cultural diversity is a big part of that picture.

These are lessons relevant to those in the creative and cultural sector but they should also be front of mind for anyone trying to run the country right now.

Effective engagement requires clear understanding

Understanding the shape, dynamics and direction of this rapidly emerging creative and cultural sector is crucial to being part of it and to engaging with it from whatever perspective. One of the main reasons the Government response to the pandemic had such a disproportionately devastating impact on the creative and cultural sector was that the Government didn’t understand that it is a broad economic sector, that reaches far beyond the narrow universe of grant-funding that the Government is familiar with.

Amongst all the bailouts, handouts and leg ups in response to the pandemic, the creative and cultural sector was largely omitted. The relief package did not cover most of those in it. Due to the Government restrictions to deal with the COVID-19 virus, within a short period 47% of the Arts and Recreation Services sector had closed down, higher than any other except for Accommodation and Food Services. This is not surprising, given the fact that the restrictions immediately impacted on performances and events. So many in the creative sector have employment patterns that consist of a life-time of short-terms contracts across a number of employers or do not work as companies with ABNs, that most are not eligible for what’s on offer.

'While everyone is locked down at home watching television, reading books and listening to music, at the same time the people who produce all these have been out of work indefinitely. The creative sector is called upon whenever it is needed, but the response in turn when it is under threat is sorely lacking.'

Simple research and forecasting might have shown this – if anyone cared. Ironically during disasters like bushfires, this same sector has risen to the occasion in many situations, playing an important role in helping community recovery. Even more ironic, while everyone is locked down at home watching television, reading books and listening to music, at the same time the people who produce all these have been out of work indefinitely. The creative sector is called upon whenever it is needed, but the response in turn when it is under threat is sorely lacking.

The Government didn’t completely ignore the creative sector. Yet its response showed a great deal about how it sees the sector and the Government’s relationship with it. It is almost completely along the lines of a funding source that provides grants to the arts – it is either grants funding or charity, as evidenced by its support for Support Act, the worthwhile body that assists performers in need. It relied to a large extent on the response of its main national arts funding body, the Australia Council, yet given the limitations of funding available through that organisation, it’s part of the whole arts funding model approach, rather than an industry sector approach.

The importance of regionalism in an increasingly globalised world

As globalism proceeds apace, the counter-balancing world of the local and regional is becoming more important, anchoring us firmly in the places where we reside and create, where culture is made and lived. This will be particularly the case as the longer-term impact of the global pandemic unfolds.

Australia culture as a whole is itself in many ways a fragile culture – in a world where American stories (and English historical dramas) are increasingly the shared stories of the world, or at least the English-speaking world. There is common ground in a two-sided culture, both dynamic and contemporary and local and also jostling to be seen amongst other cultures on the world stage.

The 2016 Census showed that nearly half (49 per cent) of all Australians had either been born overseas or one or both parents had been born overseas. That number continues to increase each year, so it is likely already higher. Our cultural diversity, from the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations, cultures and languages which underpin Australian culture, bolstered by the waves of migration, is an important national asset.

'As globalism proceeds apace, the counter-balancing world of the local and regional is becoming more important, anchoring us firmly in the places where we reside and create, where culture is made and lived. This will be particularly the case as the longer-term impact of the global pandemic unfolds.'

It also gives us an entrée into the countries and cultures from which migrants come. If we are indeed entering the Asian Century and a world where countries such as China will become increasingly important, we need every positive feature we have going for us to make the most of the opportunities presented.

In the tradition of building on our diverse histories we could do worse than follow the path of the ancient Yolngu people of East Arnhem Land, who built a thriving trade and cultural interchange with the Macassans from the northern islands which much later became Indonesia. We celebrate the Asian Century, yet it began much earlier than we realise.

Building creative regions and regional cities

Across Australia, local communities facing major economic and social challenges have become interested in the joint potential of regional arts and culture and local creative industries to contribute to or often lead regional revival. This has paralleled the increasing importance of our major cities as economic hubs and centres of innovation, though it will be interesting to see the longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on our fascination with life in cities.

In our local community here in Canberra – which of course just happens to also be the national capital – this issue is an immediate practical one. The potential role of creative industries, particularly design, in helping establish Canberra as a cool capital, both large enough and small enough to be a liveable city, has been a strategic focus of DESIGN Canberra, a major initiative of Craft ACT.

Near neighbour New Zealand has shown how smaller cities, remote from the traditional centres of film industry dominance, could establish a major, high profile niche in a global industry. In the contemporary globalised world, as long as countries and cities can survive the inevitable negative impact of the globalising process, expertise, specialist skills and industry pockets can occur just about anywhere, as long as you have connectivity, talent and a framework of support that makes it possible.

In New Zealand landmarks of popular culture, like Lord of the Rings and remakes of Planet of the Apes, spring from the sprawling operations of creative firm, Weta, which based just outside the capital, Wellington, characterises the city. Instead of the traditional industries that often dominate a town and its imagination, like the railways or meatworks or the car plant or, in Tasmania, the Hydro Electricity Commission, there is Weta. My nephew works for Weta, after time in Vancouver producing special effects for US film companies for films you would all know. He is part of the contemporary global creative talent pool, which will become increasingly important, even with the setbacks and lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic.

'Near neighbour New Zealand has shown how smaller cities, remote from the traditional centres of film industry dominance, could establish a major, high profile niche

in a global industry. In the contemporary globalised world, as long as

countries and cities can survive the inevitable negative impact of the

globalising process, expertise, specialist skills and industry pockets

can occur just about anywhere, as long as you have connectivity, talent

and a framework of support that makes it possible.'

The presence of these creative firms has unexpected spinoffs. Weta has also worked closely with the national flagship museum, Te Papa Tongarewa, on such things as an exhibition about the role of New Zealand troops in the Gallipoli Campaign. Weta Workshop has co-operated closely with Te Papa, applying contemporary digital film-making approaches, skills, techniques and technology to enliven and underline the personal stories underpinning exhibitions.

The New Zealand experience has been replicated elsewhere in different forms. A Marimekko exhibition at the Bendigo Gallery last year showed how a small country like Finland on the edges of the mainstream could become a global design force by staying true to its language, locality and culture – the things that make it distinctive in a crowded, noisy marketplace dominated by big, cashed up players.

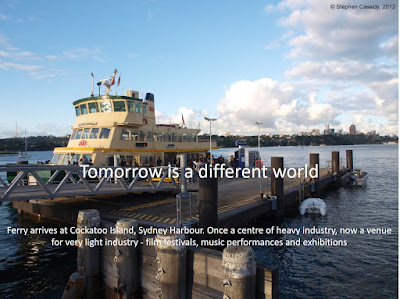

Tomorrow is a different world

To meet the challenges of the digital world, those working in the creative and cultural sector have for the last few decades been making wholesale changes to the ways they produce, integrating new approaches and techniques across art-forms with reworked traditional ways to produce a new paradigm for artistic and cultural practice. As part of this an artist may move between their own practice, work in a community context and semi-commercial work as a designer. Traditional artform boundaries are also changing. The so-called 360 degree commissioning familiar to the film world is being more broadly applied across artforms as content is repurposed and reused to produce the book, the film, the game, the website and the T-shirt of the same content.

These features of the digital world also point to a new integrated approach by cultural organisations to all aspects of their work. In the new environment artistic programs, membership, online presence, partnerships and marketing, and promotion and sales have to interact seamlessly so each reinforces the other, as a way of multiplying the impact and reach of relatively limited government support. The global pandemic has both required more of this and been better survived because of these decades of changing practice.

'These features of the digital world also point to a new integrated

approach by cultural organisations to all aspects of their work. In the

new environment artistic programs, membership, online presence,

partnerships and marketing, and promotion and sales have to interact

seamlessly so each reinforces the other, as a way of multiplying the

impact and reach of relatively limited government support.'

When I hear the call to get back to normal, I think ‘what was normal about the old normal?’ The sudden shutdown of large sectors of the economy highlighted drastically how precarious was the situation of large parts of Australian society, in particular but not exclusively, the creative sector.

The creative and cultural sector has been applying its lateral thinking to imagining how a new world post-pandemic might work. We can learn a lot from and contribute a lot to those in the hospitality sector, who in many ways are in a similar situation to those in the creative world. Both sectors depend on people coming together in crowds to share experiences.

Essential skills for the modern cultural professional

The modern emerging professional in the creative and cultural sector needs a strong grasp of a set of essential and interrelated skills which are likely to be invaluable wherever you work across the sector: building strong and diverse audiences, identifying potential partners and building broad partnerships and alliances, understanding the crucial importance of distribution for survival and growth, identifying funding sources and understanding the importance of intellectual property; broadening the financial base of organisations, extending entrepreneurial approaches.

In a period of great upheaval in the arts, we need to move away from thinking about leadership as a position (in a hierarchical structure, for example) and instead think about it as an approach or process.

Starting with an understanding of the issues that produces a need for policy, programs or projects, this understanding and the commitment which flows from it, makes it possible to build partnerships, engage stakeholders and achieve outcomes. A policy framework provides a way of seeing the social landscape and the relationships that cross it in different ways. It’s how organisations, parts of organisations, regions, governments and countries are transformed from one situation to another – hopefully an improved one. Leadership consists of providing direction and motivation to inform action to shape your part of the world to match a vision of possibilities. It makes a statement about valuing an area and being committed to doing something in that space.

While individuals will not necessarily be responsible for the whole range of development areas, they will need to be strategically literate in all of them.

It is also increasingly important to understand the importance of creative roles in organisations for which creativity and culture are not the core business.

In trying to foresee the future, I’ve always been fascinated by the profound if simple taxonomy and its relationship to risk: ‘known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns’, which is relevant to anyone in their career – even if when I first heard it used it was by Donald Rumsfeld, one of the architects of the Iraq War, though it’s much older.

Importance of a strategic view

Above all, in a world that’s so often about the short-term, it’s important to have a strategic view and to think big, think broad and think creative. Asked what he thought was the long term impact of the French Revolution, former Premier of China, Chou En-Lai, reputedly replied ‘Too soon to tell’. Now that’s what a strategic view looks like.

© Stephen Cassidy 2021

See also

Updates on creativity and culture an email away

‘After many

decades working across the Australian cultural sector, I have been

regularly posting to my suite of blogs about creativity and culture,

ever since I first set them up over 10 years ago. You can follow any of

the blogs through email updates, which are sent from time to time. If

you don’t already follow my blogs and you want to take advantage of this

service, you can simply add your email address to the blog page, and

then confirm that you want to receive updates when you receive the

follow up email. If you want to make sure you don’t miss any of my

updates, simply select the blogs you are interested in and set up the

update by adding your email’, Updates on creativity and culture an email away.

An everyday life worth living – indefinite articles for a clean, clever and creative future

‘My

blog “indefinite article” is irreverent writing about contemporary

Australian society, popular culture, the creative economy and the

digital and online world – life in the trenches and on the beaches of

the information age. Over the last ten years I have published 166

articles about creativity and culture on the blog. This is a list of all

the articles I have published there, broken down into categories, with a

brief summary of each article. They range from the national cultural

landscape to popular culture, from artists and arts organisations to

cultural institutions, cultural policy and arts funding, the cultural

economy and creative industries, First Nations culture, cultural

diversity, cities and regions, Australia society, government, Canberra

and international issues – the whole range of contemporary Australian

creativity and culture’, An everyday life worth living – indefinite articles for a clean, clever and creative future.

Beyond a joke – surviving troubled times

‘We

live in troubled times – but then can anyone ever say that they lived in

times that weren’t troubled? For most of my life Australia has suffered

mediocre politicians and politics – with the odd brief exceptions – and

it seems our current times are no different. Australia has never really

managed to realise its potential. As a nation it seems to be two

different countries going in opposite directions – one into the future

and the other into the past. It looks as though we’ll be mired in this

latest stretch of mediocrity for some time and the only consolation will

be creativity, gardening and humour’, Beyond a joke – surviving troubled times.

Labor election victory means renewed approach for Australian arts and culture support

‘Almost

a decade of Coalition Government has ended, with a complex and

ground-breaking result. During that long period the substantial and

detailed work to develop a national cultural policy under the Rudd and

then Gillard Labor Governments was sidelined. A strategic,

comprehensive, long-term approach to support by national Government for

Australian culture and creativity in its broadest sense was largely

absent. Now we are likely to see a return – finally – to some of the

central principles that underpinned ‘Creative Australia’, the blueprint

that represented the Labor Government response to Australia’s creative

sector’, Labor election victory means renewed approach for Australian arts and culture support.

Revhead heaven – travelling together into the mobile future

‘Cars are at the heart of everyday Australian life. Even if they don’t

interest you all that much, or even if you mainly use public transport,

you probably also use a car regularly. The Sunday drive, the regional

road tour, the daily commute are all as Australian as burnt toast and

peeling sunburn. The annual Summernats road extravaganza in Australia’s

national capital celebrates this mobile culture. With some imagination,

it could be even more – celebrating a central, while challenging, part

of contemporary Australian popular culture’, Revhead heaven – travelling together into the mobile future.

Flight of the wild geese – Australia’s place in the world of global talent

‘As

the global pandemic has unfolded, I have been struck by how out of

touch a large number of Australians are with Australia’s place in the

world. Before the pandemic many Australians had become used to

travelling overseas regularly – and spending large amounts of money

while there – but we seem to think that our interaction with the global

world is all about discretionary leisure travel. In contrast,

increasingly many Australians were travelling – and living – overseas

because their jobs required it. Whether working for multinational

companies that have branches in Australia or Australian companies trying

to break into global markets, Australian talent often needs to be

somewhere else than here to make the most of opportunities for

Australia. Not only technology, but even more importantly, talent, will

be crucial to the economy of the future’, Flight of the wild geese – Australia’s place in the world of global talent.

‘When we start to think about the economy of the future – and the clean and clever jobs that make it up – we encounter a confusing array of ideas and terms. Innovation, the knowledge economy, the creative economy, creative industries and the cultural economy are all used, often interchangeably. Over the years my own thinking about them has changed and I thought it would be useful to try to clarify how they are all related’, Understanding the economy of the future – innovation and its place in the knowledge economy, creative economy, creative industries and cultural economy.

Always was, always will be – a welcome long view in NAIDOC week

‘Being involved with Australian culture means being involved in one way or another with First Nations arts, culture and languages – it’s such a central and dynamic part of the cultural landscape. First Nations culture has significance for First Nations communities, but it also has powerful implications for Australian culture generally. NAIDOC Week is a central part of that cultural landscape’, Always was, always will be – a welcome long view in NAIDOC week.

‘Given the Government cannot avoid spending enormous sums of money if it is to be in any way capable and competent, this is an unparalleled opportunity to remake Australia for the future. Usually opportunities such as this only arise in rebuilding a country and an economy after a world war. It is a perfect moment to create the sort of clean, clever and creative economy that will take us forward in the global world for the next hundred years. Unfortunately a failure of imagination and a lack of innovative ambition will probably ensure this doesn’t happen any time soon’, Remaking the world we know – for better or worse.

The old normal was abnormal – survival lessons for a new riskier world

‘When I hear the call to get back to normal, I think ‘what was normal

about the old normal?’ The sudden shutdown of large sectors of the

economy highlighted drastically how precarious was the situation of vast

chunks of Australian society, in particular but not exclusively, the

creative sector. The business models implemented by the Government to

help businesses survive and employees keep their jobs didn’t work at all

for those who had already been happily left at – or even deliberately

pushed to – the margins of society and the economy. In good times the

creative sector is flexible and fast at responding. In bad times it is a

disaster, as the failure of the COVID-19 support packages for the

sector shows’, The old normal was abnormal – survival lessons for a new riskier world.

Cut to the bone – the accelerating decline of our major cultural

institutions and its impact on Australia’s national heritage and economy

‘I always thought that long after all else has gone, after government

has pruned and prioritised and slashed and bashed arts and cultural

support, the national cultural institutions would still remain. They are

one of the largest single items of Australian Government cultural

funding and one of the longest supported and they would be likely to be

the last to go, even with the most miserly and mean-spirited and short

sighted of governments. However, in a finale to a series of cumulative

cuts over recent years, they have seen their capabilities to carry out

their essential core roles eroded beyond repair. The long term impact of

these cumulative changes will be major and unexpected, magnifying over

time as each small change reinforces the others. The likelihood is that

this will lead to irreversible damage to the contemporary culture and

cultural heritage of the nation at a crucial crossroads in its

history’, Cut

to the bone – the accelerating decline of our major cultural

institutions and its impact on Australia’s national heritage and economy.

Better than sport? The tricky business of valuing Australia’s arts and culture

‘Understanding,

assessing and communicating the broad value of arts and culture is a

major and ongoing task. There has been an immense amount of work already

carried out. The challenge is to understand some of the pitfalls of

research and the mechanisms and motivations that underpin it. Research

and evaluation is invaluable for all organisations but it is

particularly important for Government. The experience of researching

arts and culture in Government is of much broader relevance, as the arts

and culture sector navigates the tricky task of building a

comprehensive understanding in each locality of the broader benefits of

arts and culture. The latest Arts restructure makes this even more

urgent.’, Better than sport? The tricky business of valuing Australia’s arts and culture.

Crossing boundaries – the unlimited landscape of creativity

‘When I was visiting Paris last year, there was one thing I wanted to do

before I returned home – visit the renowned French bakery that had

trained a Melbourne woman who had abandoned the high stakes of Formula

One racing to become a top croissant maker. She had decided that being

an engineer in the world of elite car racing was not for her, but rather

that her future lay in the malleable universe of pastry. Crossing

boundaries of many kinds and traversing the borders of differing

countries and cultures, she built a radically different future to the

one she first envisaged’, Crossing boundaries – the unlimited landscape of creativity.

Creativity and culture in change: Change in creativity and culture

‘A vast transformation of contemporary culture not seen since the

breakdown of traditional arts and crafts in the industrial revolution is

under way due to the impact of the digital and online environment.

Artists, culture managers and cultural specialists today are confronted

with radically different challenges and opportunities to those they

faced in the 20th Century. There are a number of strategic forces which

we need to take account of in career planning and in working in or

running cultural organisations’, Presentation at ‘Creative and Cultural

Futures: Leadership and Change’ – a symposium exploring the critical

issues driving change in the creative and cultural sector, University of

Canberra, October 2018, Creativity and culture in change: Change in creativity and culture.

‘With a Coalition Government which now stands a far better chance of being re-elected for a second term, the transfer of the Commonwealth’s Arts Ministry to Communications helps get arts and culture back onto larger and more contemporary agendas. This move reflects that fact that the new industries in the knowledge economy of the future, with its core of creative industries and its links to our cultural landscape, are both clever and clean. Where they differ completely from other knowledge economy sectors is that, because they are based on content, they draw on, intersect with and contribute to Australia’s national and local culture and are a central part of projecting Australia’s story to ourselves and to the world. In that sense they have a strategic importance that other sectors do not’, Full circle – where next for Australian national arts and culture support in the 21st Century?

‘The endless attrition of the ‘efficiency dividend’, with its long-term debilitating impact on our major national cultural institutions, continues to do harm. With the periodic announcement of job losses, more and more valuable expertise is increasingly lost and important programs affected. This will undermine the ability of these institutions to care for our heritage and to provide access to their collections for Australians across the country. The long term impact of these cumulative changes will be major and unexpected, magnifying over time as each small change reinforces the others. At some point Australians will ask where valued and important programs have gone and how critical institutions have managed to diminish to the point where return will not be possible,’ Endless attrition at major collections institutions undermines our cultural future.

Cut to the bone – the accelerating decline of our major cultural

institutions and its impact on Australia’s national heritage and economy

‘I always thought that long after all else has gone, after government

has pruned and prioritised and slashed and bashed arts and cultural

support, the national cultural institutions would still remain. They are

one of the largest single items of Australian Government cultural

funding and one of the longest supported and they would be likely to be

the last to go, even with the most miserly and mean-spirited and short

sighted of governments. However, in a finale to a series of cumulative

cuts over recent years, they have seen their capabilities to carry out

their essential core roles eroded beyond repair. The long term impact of

these cumulative changes will be major and unexpected, magnifying over

time as each small change reinforces the others. The likelihood is that

this will lead to irreversible damage to the contemporary culture and

cultural heritage of the nation at a crucial crossroads in its

history’, Cut

to the bone – the accelerating decline of our major cultural

institutions and its impact on Australia’s national heritage and economy.

‘When I first heard that Victorian regional gallery, Bendigo Art Gallery, was planning an exhibition about contemporary Indigenous fashion I was impressed. The Gallery has had a long history of fashion exhibitions, drawing on its own collection and in partnership with other institutions, notably the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It is fascinating to consider how a leading regional Australian museum and an internationally renowned museum on the global stage, while in many ways so different, have so much in common. The exhibition is far more than a single event in a Victorian regional centre – it is an expression of a much broader contemporary Indigenous fashion phenomenon nation-wide. It hints at the potential of the creative economy and creative industries to build stronger communities. Both the economic importance and the community and social importance of creativity and culture are tightly interlinked because of the way in which creativity and culture are integral to everyday life and the essential activities that make it up’, After a fashion – creative industries from First Nations culture.

‘World-shaking events can completely reframe your perspective. When I drove from Canberra to Adelaide and Kangaroo Island in March this year, everyone was being urged to visit regional centres to help them recover from the devastating bushfires. Only weeks later, as I was heading home – via Victoria, a State entering lockdown as I passed through – everybody was being encouraged to stay home to help stop the spread of disease. Back in Canberra I had been involved in a long-running effort to have the city listed as a UNESCO City of Design. The new reality that threatened to overshadow that effort was the global COVID-19 pandemic. Ironically that pandemic had originated in the Chinese city of Wuhan, which as I discovered, was itself a City of Design in the global UNESCO Creative Cities Network’, A world turned upside down – UNESCO Creative City of Design Wuhan.

‘Making a living in the developing creative economy is no easy task. For a viable career, flexibility and creativity are crucial. For this a strategic outlook and a grasp of the major long-term forces shaping Australian creativity and culture is essential. To help foster this amongst emerging cultural sector practitioners, a new flagship course, a Master of Arts in Creative and Cultural Futures, was launched at the University of Canberra in 2019, building on earlier experiments in aligning research and analysis with real world cultural sector experience’, Making a living – building careers in creative and cultural futures.

Industries of the future help tell stories of the past – Weta at work in the shaky isles

‘After three weeks travelling round the North Island of New Zealand, I’ve had more time to reflect on the importance of the clean and clever industries of the future and the skilled knowledge workers who make them. In the capital, Wellington, instead of the traditional industries that once often dominated a town, like the railways or meatworks or the car plant or, in Tasmania, the Hydro Electricity Commission, there was Weta. It’s clear that the industries of the future can thrive in unexpected locations. Expertise, specialist skills and industry pockets can occur just about anywhere, as long as you have connectivity, talent and a framework of support that makes it possible. These skills which Weta depends on for its livelihood are also being used to tell important stories from the past’, Industries of the future help tell stories of the past – Weta at work in the shaky isles.

Designs on the future – how Australia’s designed city has global plans

‘In many ways design is a central part of the vocabulary of our time and integrally related to so many powerful social and economic forces – creative industries, popular culture, the digital transformation of society. Design is often misunderstood or overlooked and it's universal vocabulary and pervasive nature is not widely understood, especially by government. In a rapidly changing world, there is a constant tussle between the local and the national (not to mention the international). This all comes together in the vision for the future that is Design Canberra, a celebration of all things design, with preparations well underway for a month long festival this year. The ultimate vision of Craft ACT for Canberra is to add another major annual event to Floriade, Enlighten and the Multicultural Festival, filling a gap between them and complementing them all’, Designs on the future – how Australia’s designed city has global plans.

Creativity at work – economic engine for our cities

‘It is becoming abundantly clear that in our contemporary world two critical things will help shape the way we make a living – and our economy overall. The first is the central role of cities in generating wealth. The second is the knowledge economy of the future and, more particularly, the creative industries that sit at its heart. In Sydney, Australia’s largest city, both of these come together in a scattering of evolving creative clusters – concentrations of creative individuals and small businesses, clumped together in geographic proximity. This development is part of a national and world-wide trend which has profound implications’, Creativity at work – economic engine for our cities.

‘Across Australia, local communities facing major economic and social challenges have become interested in the joint potential of regional arts and local creative industries to contribute to or often lead regional revival. This has paralleled the increasing importance of our major cities as economic hubs and centres of innovation’, The immense potential of creative industries for regional revival.

Design for policy innovation – from the world of design to designing the world

The clever business of creativity: the experience of supporting Australia's industries of the future

‘The swan song of the Creative Industries Innovation Centre, ‘Creative Business in Australia’, outlines the experience of five years supporting Australia’s creative industries. Case studies and wide-ranging analysis explain the critical importance of these industries to Australia’s future. The knowledge economy of the future, with its core of creative industries and its links to our cultural landscape, is both clever and clean. Where the creative industries differ completely from other knowledge economy sectors is that, because they are based on content, they draw on, intersect with and contribute to Australia’s national and local culture’, The clever business of creativity: the experience of supporting Australia's industries of the future.

My nephew just got a job with Weta – the long road of the interconnected world

‘My nephew just got a job in Wellington New Zealand with Weta Digital, which makes the digital effects for Peter Jackson’s epics. Expertise, specialist skills and industry pockets can occur just about anywhere, as long as you have connectivity, talent and a framework of support that makes it possible. This is part of the new knowledge economy of the future, with its core of creative industries and its links to our cultural landscape. Increasingly the industries of the future are both clever and clean. At their heart are the developing creative industries which are based on the power of creativity and are a critical part of Australia’s future – innovative, in most cases centred on small business and closely linked to the profile of Australia as a clever country, both domestically and internationally. This is transforming the political landscape of Australia, challenging old political franchises and upping the stakes in the offerings department’, My nephew just got a job with Weta – the long road of the interconnected world.

‘The developing creative industries are a critical part of Australia’s future – clean, innovative, at their core based on small business and closely linked to the profile of Australia as a clever country, both domestically and internationally.’ Creative industries critical to vitality of Australian culture.

Applied creativity

‘I have been dealing with the issue of creativity for as long as I can remember. Recently, I have had to deal with a new concept—innovation. All too often, creativity is confused with innovation. A number of writers about innovation have made the point that innovation and creativity are different. In their view, innovation involves taking a creative idea and commercialising it. If we look more broadly, we see that innovation may not necessarily involve only commercialising ideas. Instead the core feature is application—innovation is applied creativity. Even ideas that may seem very radical can slip into the wider culture in unexpected ways’, Applied creativity.

Creative industries – applied arts and sciences

‘The nineteenth century fascination with applied arts and sciences — the economic application of nature, arts and sciences — and the intersection of these diverse areas and their role in technological innovation are as relevant today for our creative industries. From the Garden Palace, home of Australia’s first international exhibition in 1879, to the Economic Gardens in Adelaide’s Botanic Gardens these collections and exhibitions lay the basis for modern Australian industry. The vast Garden Palace building in the Sydney Botanic Gardens was the Australian version of the great Victorian-era industrial expositions, where, in huge palaces of glass, steel and timber, industry, invention, science, the arts and nature all intersected and overlapped. Despite burning to the ground, it went on to become the inspiration for what eventually became the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences — the Powerhouse Museum’, Creative Industries.

No comments:

Post a Comment